Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

This week, we cover Lord Dunsany’s “How Nuth Would Have Worked His Art Upon the Gnoles,” first published in his 1912 collection The Book of Wonder. Spoilers ahead.

“And often when I see some huge, new house full of old furniture and portraits from other ages, I say to myself, ‘These mouldering chairs, these full-length ancestors and carved mahogany are the produce of the incomparable Nuth.’”

To those outside the “magic circle” of the burglary business, Nuth’s name is little known, but such is his incomparable skill that, unlike his rivals, he has no need to advertise. Many claim it’s Slith who stands alone, incomparable, but Slith lived long ago, and his surprising doom may cast an exaggerated glamour on his merits.

Nuth’s terms are moderate, cash upon delivery and so much in blackmail thereafter. When our narrator sees new houses full of fine old furniture, he assumes this plunder is the “produce” of Nuth. For has not our narrator seen wind-tossed shadows move more noisily than Nuth?

As our story begins, Nuth is living rent-free in Belgravia Square, where the property’s caretaker remarks to prospective buyers that it would be the finest house in London, if it weren’t for the drains. One spring morning an old lady comes to see Nuth, bringing along her large and awkward son. Young Tommy Tonker is already in business but wants to better himself; Mrs. Tonker hopes Nuth will take him as apprentice. Nuth, impressed by Tonker’s reference from a jeweller with whom the burglar is well acquainted, agrees to the proposal.

By slow degrees Nuth teaches Tonker the art of burglary, until his apprentice can soundlessly cross bare floors littered with obstacles in the dark, and silently climb creaky stairs. Their business prospers, culminating in a certain transaction with Lord Castlenorman at his Surrey residence, in which Tonker follows his master’s instructions so well that not even rumor whispers Nuth’s name in connection with the affair. Emboldened with this success, Nuth aspires to a deed no burglar has dared before: burgling the house of the gnoles.

So nearly insane with pride is Tonker over his part in the Castlenorman matter, so deeply does he venerate Nuth, that after respectful objections he allows himself to be persuaded.

Now, the gnoles live in a narrow, lofty house in a dreadful wood which no humans have entered for a hundred years, not even poachers intent on snaring elves. One doesn’t trespass twice in the dells of the gnoles. The nearest village of men puts the backs of its houses to the wood, with no doors or windows facing in that direction, and the villagers do not speak of the place. Nevertheless, on a windy October morning, Nuth and Tonker slip in among the trees.

They carry no firearms, for Nuth knows the sound of a shot would “bring everything down on us.” They plan to procure two of the enormous emeralds with which the gnoles ornament their house, with the caveat that if the stones prove too heavy, they’ll drop one at once rather than risk slowing their escape. In silence, they come upon the centuried skeleton of a poacher nailed to the door of an oak tree. The occasional fairy scuttles away. Once Tonker steps on a dry stick, and they must lie still for twenty minutes. Sunset comes with an ominous flare. Fitful starlight follows. When they come at last to the lean high house of the gnoles, Nuth perceives a certain look in the sky “worse than a spoken doom.” Tonker is encouraged by the house’s silence, but Nuth knows it is too silent.

Nevertheless, he sends Tonker up a ladder to an old green casement, laden with the tools of their trade. When the lad touches the withered boards of the house, the stillness that has heartened him becomes “unearthly like the touch of a ghoul.” Leaves fall mute; the breeze stills; no creature stirs, Nuth included. As he should have done long before, Tonker decides to leave the gnoles’ emeralds untouched. Better to quit the dreadful wood at once and retire from the burglar business altogether!

Tonker climbs down, but the gnoles have been watching him out of holes bored into the surrounding trees. Now they emerge and seize Tonker from behind, and the silence is broken by his screams. Where they take him it is not good to ask, nor will our narrator say what they do with him.

Nuth looks on from a corner of the house, rubbing his chin with mild surprise, for the trick of the tree holes is new to him. Then he steals away through the dreadful wood.

Gentle reader may ask our narrator if the gnoles caught Nuth. To which childish question, our narrator can only reply, “Nobody ever catches Nuth.”

What’s Cyclopean: Tonker expostulates respectfully about the plan to steal from the gnoles.

The Degenerate Dutch: Our narrator comments somewhat snidely on the habits of both the rich and men of various businesses; beyond these class and professional distinctions the only difference noted among humans is whether they celebrate the Sabbath at a convenient time for visiting burglars.

Weirdbuilding: Gnoles appear later in a story by Margaret St. Clair, and gnolls (possibly related) appear as a species in Dungeons and Dragons. You might poach elves or see a fairy scuttle away in the woods where they dwell; gnoles themselves are something else.

Libronomicon: No books this week; Nuth writes only “laboriously” as forgery is not his line.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Tonker is “nearly insane with pride” over his success with Lord Castlenorman, and thus vulnerable to hubris.

Anne’s Commentary

After reading “How Nuth Would Have Practised His Art Upon The Gnoles” (hereafter referred to as a word-count-sparing “Nuth”), I decided to binge the whole of the 1912 collection in which it originally appeared. The Book of Wonder has some, Wonders, that is—stories that justify the influence Lord Dunsany has had on writers from Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith, to J. R. R. Tolkien and Arthur C. Clarke, to Neil Gaiman and Guillermo Del Toro. Ursula K. Le Guin wryly mimics Dunsany’s own wry style when she dubs him “The First Terrible Fate that Awaiteth Unwary Beginners in Fantasy.” When he’s at the top of his game, Dunsany’s at the top of the game where weird fiction of the picturesque or eerie or droll (often all at once) is concerned. At these times, he’s well worth emulating.

At other times Dunsany just gets so Dunsanian that he’s his own “First Terrible Fate.” Maybe binge-reading him isn’t a good idea. Gobbling (Gibbelin-like) The Book of Wonders, I found the stories blurring into each other. I was forgetting which was which, though I continued to recognize categories: Otherworldly travelogues (“The Bride of the Man-Horse” and “The Quest of the Queen’s Tears”), stories connected at the “edges” with Our Own World (“Nuth”), tales (a good chunk!) dealing with the Fateful Meeting of Ordinary British People with Other Worlds (“The Coronation of Mr. Thomas Shap,” “Miss Cubbidge and the Dragon,” and “The Wonderful Window.”)

By the way, if you’re wondering about that legendary thief Slith with whom some compare the incomparable Nuth, you can read about his “surprising doom” in “Probable Adventure of the Three Literary Men.” Like Nuth, Slith never gets caught. Unlike Nuth, he pays a very high price for his final escape. Another legendary thief, Thangobrind the Jeweller, meets a dire end in his “Distressing Tale”–not a story for arachnophobes. The thief’s life is a hazardous one in Dunsany’s work, but Nuth the nimble, more silent than shadow, makes it work. In part, as in today’s story, by judicious delegation and decoying.

If there’s one thing more dangerous than being a burglar, it’s being a burglar’s apprentice. What was Mrs. Tonker thinking?

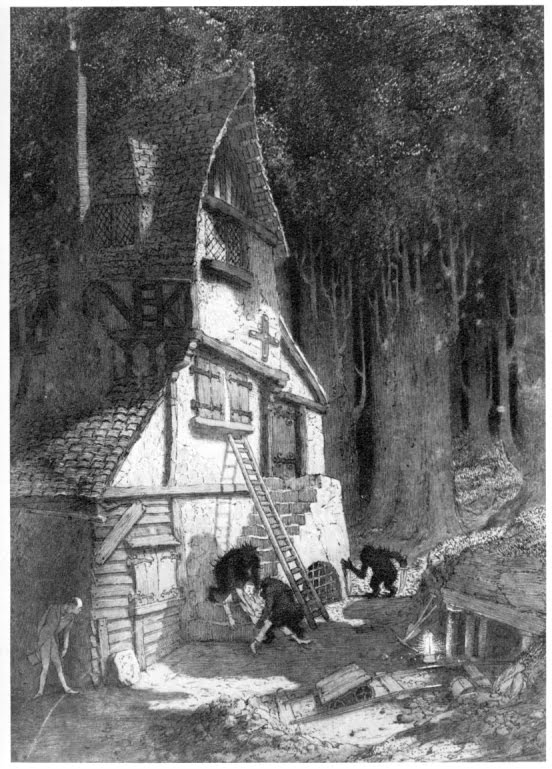

The Book of Wonders provides an interesting example of art imitating art. Dunsany writes that his frequent illustrator Sydney Sime was discouraged by the tiresomely mundane assignments editors were offering him. Dunsany’s solution: Sime should draw whatever he liked, and then Dunsany would base stories on the pictures, rather than the other way around—this procedure, he hoped, would add to the “mystery” of the work. How far the two stuck to this scheme I don’t know, but “Nuth” is one of the stories with a splendidly “mysterious” Sime illustration. It shows a “narrow, lofty” house with timbered walls and rough stone steps leading to a high front door. I don’t see any emeralds encrusting the exterior; the sole decoration is a wooden cross above the door. A dubious-looking outbuilding is sunk into a low mound before the house; trees of an unwholesomely ancient aspect fade into a benighted background.

For figures, Sime provides a tall, balding fellow peering around the corner of the house. You could say his attitude is one of “mild surprise” rather than alarm, although it’s an alarming scene unfolding at the foot of a ladder leaning up to shuttered windows. A younger man sprawls in the ungentle grip of two squat creatures combining a basically human outline with aspects vaguely canine or baboonish. They are solid black, a little blurred at the edges, like dissolving shadows or holes punched into the void between worlds. Another such creature approaches from the direction of the trees, hunched, forepaws clenched in obvious ire and/or glee. There may also be glowing eyes in the dark forest, hard to tell in the reproductions I’ve accessed.

So the picture certainly suggests a tale of burglary gone very wrong for the burglars. The lead-up to this awful climax is all Dunsany at his best, combining the droll with the horrifying, a satirical take on modern society with a nostalgia for the past of legend rather than reality. Master thief Nuth is at home in a turn-of-the-century London full of parvenues hungry for faux-ancestral credentials. He also has access to Other places at the edge of Terra Cognita; these Other places aren’t entirely Incognito to him, though he still has much to learn, like the gnoles’ stratagem of spying from tree holes.

Those tricksy gnoles! What are they, anyway? There are gnolls in Dungeons & Dragons, described in a 1974 set as “a cross between gnomes and trolls (…perhaps Lord Dunsany did not really make it all that clear)” True, Dunsany deliberately refrains from describing the gnoles, which not only teases reader imagination but has the effect of making gnoles more “real”–why describe what everyone of any Otherworldly erudition knows the appearance of? In Middle English and English dialect, noll refers to the head or nape. Slang has many definitions for noll, from the sexual to the derogatory. In French, gnôle means “an illicitly distilled and usually inferior alcoholic liquor,” in other words, bad booze. Dunsany’s gnoles are very bad booze indeed in their effects on trespassers.

In her “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles,” Margaret St. Clair does describe the cryptic critters, or at least their “senior.” He looks “a little like a Jerusalem artichoke made of India rubber, and he has small red eyes which are faceted in the same way that gemstones are.” She also lets us know the senior gnole has a “little fanged mouth” and a “narrow ribbony tongue. Also tentacles, which the unfortunate rope salesman finds are more supple and strong than any of his cordages. At least the gnoles do him the courtesy of slaughtering him for the table “in quite a humane manner” and decorating his serving plank with fancy knotwork twisted from his own samples.

I think I like Sime’s gnoles best, for they so well mirror in the graphic Dunsany’s delectable blending of the humorous and the horrific in the literary. I mean, they’re kind of cute, in a scary-ass way. What could be nicer, at a safe distance?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

How Nuth… would have worked his art? This is a story, ostensibly, about something that did happen, and did not involve Nuth actually working his art upon the gnoles. Unless… he did? In the negative space of whatever he was doing, and not getting caught at, while we were busily listening to Tonker’s screams? He’s mildly surprised by the trick with the trees, not Tonker’s fate. Maybe he’s got an emerald in his pocket.

This sort of practise must be hard on apprentices.

Or maybe—as our comfortable storyteller sits at a distance from the events—Nuth is a folkloric figure well-known to both narrator and assumed listener, if not actual reader. Perhaps there’s a whole set of stories, Anansi-style, starting “How Nuth Would Have…,” and we just happen to overhear this one through a hole in a tree.

“Nuth” strikes me at first as more fable-ish than Weird. The Fair Folk, in most of their forms, are creatures of strict rules—predictable even if cruel, even if not always successfully predicted. And “don’t steal from the powerful people living in the dark woods” is certainly an urgent moral. It’s also an old one, where the Weird tends to feel modern even in early examples. Dunsany’s leaning into the oldness instead, suggesting a whole familiar mythology backing the sparse words on the page. Contrast with Lovecraft’s transformation of fae into brain-stealing aliens—it takes a lot of words, and a certain amount of technological hand-waving. Dunsany’s added no pseudo-rational explanations for irrationality, and nothing more modern than the Tolkien-ish conceit of “burglar” as the sort of thing one advertises for.

But I keep coming back to that negative space. Dunsany makes the reader fill in the gaps, in everything from the title through the closing lines. And in those unseen spaces might be everything from a burglar cruelly sacrificing his loving apprentice, to a folktale antihero, to your certainty that you have heard of gnoles before, of course you have. Maybe you even know what they look like. This sort of trick, inviting your brain to make a complete picture where no such thing exists, then reminding you that you might have gotten it wrong, seems more expectation-violating Weird than expectation-reinforcing fable.

Open questions remain: what sort of person is our narrator, and what sort of creature is Nuth? For the latter, maybe he’s just a particularly highly-ranked part of the thieves’ guild (which presumably puts out the journals in which “others” advertise), but one does wonder if his not-getting-caught power has some magic to it. It would fit with the “folklore antihero” option, or with having a little bit of gnole blood himself.

Narrator, on the other hand, seems human but extremely ironic in his commentary on the upper classes who hire Nuth. He knows a great deal about the burglar, admires but disapproves: “such politics as I have are on the side of property” but also “he needs no words from me.” My original thought was one of the upper crust commenting on the acquisitive habits of his fellows, but now I think perhaps he serves those who sometimes prefer to hire a burglar rather than engage in sordid mercantile negotiations over a desired tapestry. An Alfred-like butler, perhaps? I notice that in failing to describe the details of Tonker’s apprenticeship he also fails to mention which of the categories that don’t need those details—if any—he falls into.

Mysteries on top of mysteries, compressed into the smallest possible file size. That’s pretty weird—and impressive—all by itself.

Next week, we continue T. Kingfisher’s The Hollow Places with Chapters 5-6, in which we explore further down the corridor that is definitely not in the Wonder Museum.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

I’m quite fond of Lord Dunsany’s Book of Wonder. I especially like Miss Cuddbridge and the Dragon.

I was actually hoping “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles” was going to get its own entry. In some ways, St. Clair’s riff on Dunsany is better than Dunsany. I especially like when she engages in her own bit of weirdbuilding: “The gnoles were watching him through the holes they had bored in the trunks of trees; it is an artful custom of theirs to which the prime authority on gnoles attests.”

I’m not sure if I ever read this one before- as you said, all Dunsany sounds alike after a while. I do remember the St. Clair story, and am off to re-read it now. And, after all, it was none of his business what the gnoles used cordage for.

I thought ‘Reginald Bretnor’ had also written about gnolls, but I was wrong- they were gnurrs.

One quibble: It was not young Tonker alone whose better judgment was affected by the theft from Lord Castlenorman. It is quite clear from the story that Nuth is irked by the way he is not accused, even in whispered rumors, of being involved. Whether this took the form of jealousy against his gifted apprentice, or rashness driven by anger about the lack of rumors, I am not sure.

I wondered for a while whether the Gnoles were related to the Gibbelins. On reflection, it seems unlikely, as the Gibbelins have, according to their story, come from somewhere else; their tower is anchored to the Lands We Know by a bridge. Also, the Gibbelins resemble humans well enough to pass amongst us undetected (they “sent spies into the cities of men to see how avarice did, and always the spies returned again to the tower saying that all was well”). The Gnoles do not seem to be quite so human-shaped, assuming Sime’s illustrations are authoritative.

Thank you for discussing Dunsany; I am a big fan.

Big Dunsany fan here. Read both stories many years back. Far as I’m concerned you can review a whole lot more of his work. When you got talking about etymology, I wondered if the gnoles were related to the grassy gnoll that was implicated in JFK conspiracy theories? Oh, all right,it was a knoll. But a reader might be forgiven for confusing gnoles, gnurrs, ghouls and knolls.

The St. Clair story was found in a midcentury Hitchcock antho containing several other masterpieces–The Desrick on Yandro [Wellman], Slime [Brennan], and several others of which all might be worth your examination. I don’t recall the title of the collection, which apparently was pretty popular once, but at least some of those stories might be found elsewhere.

@5- That’s probably where I read it too.

Anne, Ruthanna- I think re-reading some Manly Wade Wellman would be good- love his work!

My mental picture of the narrator is similar- Alfred, the butler, or perhaps one of the gentleman’s gentlemen, such as Bunter or Jeeves.

Sorry- duplicate post!

Gnolls apparently exist in D&D as a cross between gnomes and trolls.

In Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, “gnolls” are rather Orc-like in earlier books–in later books they’re pretty much animated refuse heaps with a tendency to pick anything up and an attitude problem.

Also in Discworld, “Tonker” is a slang word for the male member (cf “todger”).

On the one hand, the first fantasy that I read that I consciously thought of as “fantasy” was Lord of the Rings. I bought the Ace edition when it came out, read straight through it, felt guilty upon learning that it was unauthorized, bought the Ballantine edition, read straight through that starting with The Hobbit this time, which Ace hadn’t published. Then I read straight through the entire Ballantine Adult Fantasy series as each volume was released. The Adult Fantasy series kinda spoiled me for current fantasy, so I read a lot more science fiction as a result.

On the other hand, that was not my really first encounter with fantasy, although at the earlier point I was not self-conscious about it. In the midst of my father’s library of history books & James Thurber was a copy of The Gods of Pegana that Dad bought in 1917 when it came out. I read it when I was about 10 and I loved it. First fantasy, if you don’t count Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories. Dad had forgotten that he had it.

I really appreciate the fable nature of many of Dunsany’s stories. While I see similarities, his stories don’t blend together at all for me. Where I struggled was with his novels. The first Dunsany that Ballantine published was The King of Elfland’s Daughter, and MAN did I struggle with that.

#5: the Hitchcock collection you want is Monster Museum.

__________________________________

I actually read The Man Who Sold Rope To The Gnoles in the aforesaid Hitchcock collection long before I had ever even heard of Dunsany, and when I read the Nuth story many years later I had the feeling that it was Dunsany homaging St Clair, not the other way around. Both tales are drily funny in the line of Twain or Bierce, and if I had to choose I would put St Clair’s effort much higher.

By the way, St Clair only said the Senior Gnole, who need be leaves the house, looks like a Jerusalem artichoke, whatever that might be, etc. For all we know the Junior Gnoles might look like anything at all, and not one might look like any other. They might possess ears and not even have detachable eyes!

It seemed to me obvious that Nuth had taken on apprentices often before, and that his only purpose in doing so was to get them proficient in burglary enough to unleash them on the gnoles. Not to successfully steal from them. Oh no, that wasn’t the plan. To get caught in some new way, which Nuth could study and therefore increase his knowledge of the gnoles’ defences, until he knew enough to launch his own successful attempt. That’s why unlike the other thieves in the Book Of Wonder, Thagobrind and the one who tried to steal the hoard of the Gibbelins, Nuth gets away this time. Presumably Dunsany was describing one of his not-ultimate attempts.

There was some other, extremely bad, novel from the 80s (The Gnole by Alan Aldridge and Steve Boyett, I think) with gnoles that looked like moles and were absolutely insufferable Good Guys. Horrible.

Our man Nuth also makes an appearance in Joshua Reynolds’s The Ghoul’s Portrait, although he’d really rather not be there at all. The story itself follows the trio of ghouls sent to steal the titular artifact back from him and enact revenge. It’s a lot of fun and definitely my favourite story in Pickman’s Gallery (which is mostly very mediocre in my opinion).

Later editions of D&D made gnolls a bit more distinctive, and considerably less Dunsanian. They now look like hyena-headed men and seem to live exclusively by raiding and banditry — when they’re not working for higher-powered villains as disposable mooks, of course.

Gnolls in DnD started out as between gnomes and trolls, I believe. Nowadays they’re hyena people. There’s different interpretations from world to world, but the default tends to be monstrous, savage raiders, with a tendency to eat everything in sight- animals, captives, each other. In one edition their god was a god of hunger, and their ultimate goal is to devour everything, join with him, and then free themselves and their god of their constant burning hunger and live happily ever after. Shades of Lovecraftia there, but ultimately gnolls are what you throw at the party when you feel bad about killing orcs and goblins and cute little kobolds. No manners, no real culture, no idea of fun beyond hurting other things, each one meaner and grosser than Tolkien-style orcs and goblins.

Dunsany’s gnoles, on the other hand, seem a bit more eldritch and fae. They read like distant cousins of ghouls, who’ve abandoned the crypts and corpses for the woods and fresh meat. They’re old, and knowing, and they like to set traps and wait.

It is borne on me to my shame, on re-reading this story, that I know nothing at all about early Georgian poachers. Surely someone must have left some small volume of reminiscence and rumour that could open this shadowed chapter of history to us.

#14: The implication is that in Georgian times, a bit over a century before Dunsany was writing, there was a poacher snaring elves in that wood where the Gnoles reside. What one would do with an elf, once snared, must remain a mystery.

@14- perhaps this will help?

https://penandpension.com/2018/10/10/poachers-in-the-18th-century/

@16

Why, this is perfect! Ms Adams, you are a positive pip!

Now I imagine a poacher’s fate … the threatening gallows,

a spell in a hulk on the Thames, then transportation to

Tasmania or Botany Bay in the first days of the British

incursion. This is weirdbuilding indeed.

@15, demand wishes perhaps?

The obvious influence on Tolkien here is on his poem “The Mewlips”, which while pleasing enough isn’t his best effort. It’s much too overt.

@15 whatever it is, it clearly isn’t good for your ‘elf.

@20, there’s also the tradition of the captive fairy wife. Maybe that’s what elf poachers are after?

One also wonders whether the landed nobility would have kept up faerie habitats secretly on their estates. Oh aye, our family’s been fae-keepers for the Folkstones and Castlenormans these seven generations back. Don’t be telling, now.

(See also Miss Masham’s Repose.)

And also, how did the Fair Folk make out in the Enclosures? Did they die off, or emigrate for uncanny lands?

One also wonders whether the landed nobility would have kept up faerie habitats secretly on their estates.

@Jonathan:

For a modern take on that idea, see K.J. Kabza’s “The Ramshead Algorithm.”

There are also gnolls in one of T. Kingfisher’s settings (specifically in the Paladin books). A surprisingly nice version, actually, or at least the one we meet is pretty nice – fond of oxen and comfortably bemused by humans.

Biswapriya @@@@@ 10: This is pretty similar to my unpleasant suspicions about Nuth. Apprentices who go inside (or try to go inside) without you are expendable apprentices.

David Shallcross @@@@@ 15: Trade hostages for poached humans? Much easier than winning musical contests or holding tight/fearing not. (I’ve spent a good portion of today buried in Child Ballads for reasons.)

@@@@@ 22, Jonathan Burns:

One also wonders whether the landed nobility would have kept up faerie habitats secretly on their estates. Oh aye, our family’s been fae-keepers for the Folkstones and Castlenormans these seven generations back. Don’t be telling, now.

There’s nothing secret about them. On great estates, faerie habitats are in groves, or in plain view. There is more than one reason they are called follies.

Slight correction. This story was first published in The Sketch February 15 1911.